“He (Prakāśadharman) bears the royal glory, which brings auspicious results, in order to benefit the world and not to increase (his own) pleasure…”

Richard Salomon’s translation of a verse from the Rīsthal Inscription of Prakāśadharman, the later Aulikara ruler, dated 515 CE.1

If we try to classify the timeline of the Indo-Hunnic relations, it can be divided into three main phases. The first major event was the Hunnic attempt at an invasion of India during the time of the mighty Gupta-s in the middle of the fifth century CE that resulted in a resounding Hunnic defeat at the hands of Skandagutpa Kramāditya in an intense battle. How effective this was can be understood from the fact that the Huns or Hūṇa-s, as they were called by the ancient Indians, did not try to repeat their attempts for a considerable period of time. The Gupta-s had successfully thwarted an attempt at an invasion of the core of Indian lands. In order to understand the events of the first phase in detail, if the readers are interested, they can read a previous post of this blog – ‘Gupta-Hūṇa Relations: A Study’ in which I had attempted to analyse and summarise the opinions of various scholars on the issue.

The second phase which forms the topic of this blog post, began as soon as the end of the first one, i.e. after the defeat of the Hūṇa-s by Skandagupta. But in this phase, they were able to penetrate deep in the Indian territories under their able ruler Toramāṇa. However, despite their successes, once again an Indian ruler – Prakāśadharman, the Aulikara thwarted their chances. The third phase also starts right after the end of the first one but that is a topic for another post, though I will mention and discuss some aspects of the third phase as and when they will help to understand and clear the points regarding the second one. This fascinating aspect of Indian history has been researched by many scholars and historians, both Indian and foreign, and there also have been many new developments in recent years. In my analysis of this continuation of the Indo-Hunnic saga, I humbly try to summarise the views and opinions of these scholars.

Table of Contents & Links

- Background

- Hunnic Consolidation in the Indian North-West

- India on the Eve of the Invasion

- Archaeological & Literary Sources of the Indo-Hunnic War

- The Later or Imperial Aulikara-s & the Naigama Family

- The Invasions – An Analysis

- The Victorious Prakāśadharman

- The Effect of the Gupta-s

- The Śaiva Influence

- Conclusion

- References

- Bibliography

Figure 1 – The Prakāśāditya Coin of Toramāṇa. It has been conclusively proved by Pankaj Tandon in his seminal paper ‘The Identity of Prakāśāditya’, 2015 to belong to the Hūṇa ruler Toramāṇa; also see the discussion titled ‘Numismatics’ below. (Image Credit: Bakker, The Alkhan… 2020; 78)

Background

As stated in the introduction, the first major Indo-Hunnic battle ended with a Hunnic defeat under the leadership of Skandagupta. At that time, the Hūṇa-s had already acquired control of the north-west of the Indian subcontinent up to the region of western Punjāb (current Punjāb province of Pākistān) and after this, they had tried to expand into the core territories. But after losing the battle in around 455 CE, though they had lost their goals but they had not gone out of India completely. In fact, they were now back to the territories they had control over — i.e. north-west India up to western Punjāb. The fact that the Hūṇa-s still had control over these areas was also a reason that Skandagupta had to be on constant vigil.

The first battle had raged between the Gupta-s and a confederacy of the Hunnic powers that included Kidarite Huns (the main element) and Alchon Huns. As mentioned in a previous post – these Hunnic tribes had varying periods of co-operation and struggle between themselves even before they invaded Indian mainland. Bakker mentions that according to the numismatic evidence studied by Elizabeth Errington, curator of South and Central Asian coins at the British Museum, the Kidarites were predominant in the Peshāwar valley and Swāt and the Alkhans were in control of the main route between Peshāwar and Taxilā.2 The defeat at the hands of Skandagupta seems to have initiated another period in which the Kidarite Huns had their pre-eminent position undermined and from this began the rise of the Alchons to the position of power among the Hunnic tribes in India and an increased proportion of land was now under their control in the Indian north-west.

Hunnic Consolidation in the Indian North-West

§ The Schøyen Copper Scroll

There is however a gap of almost forty years between the last main evidence related to the Hūṇa-s i.e. the Bhītari Pillar Inscription of Skandagupta dated ~ 455 CE and when curtain rises and we again get to know some concrete details other than coinage of these Hunnic tribes. This curtain raiser evidence is called the Schøyen Copper Scroll. This is a Sanskrit document, dated to year 68 (probably of the Kaniṣka Era) and thus is considered belonging to 495/96 CE.3 Earlier its provenance was considered to be Afghānistān, but now is believed to be from Punjāb. The scroll is concerned with a Buddhist foundation (Bakker, 2020; 27) and mentions the erection of a stūpa. The donors of this scroll are one Devaputra King of Tālagāna, his father Opanda and his wife Buddh (Bakker, 2020; 27). Bakker suggest identifying Tālagāna with the Tālagang in the Punjāb, Pākistān (Bakker, 2020; 51). The scroll was authorized by the Alkhan (Bakker, 2020; 26) and mentions four of them ruling contemporaneously in the north-west of the Indian subcontinent; effectively ruling in the form of a quadrumvirate. The Alkhan princes mentioned are – mahāṣāhi Khīṅgīla, devarāja Toramāna, mahāṣāhi Mehama and mahārāja Javūkha, son of Sādavīkha (Bakker, 2020; 26). This actually corroborates the information that the coinage of the Alkhan also presents us with i.e. a same quadrumvirate except in the case of the scroll, Toramāna has been mentioned instead Lakhāna of the coinage. Based on the common coinage of these Alkhan princes found in Kashmir Smast, the quadrumvirate that we start with includes rāja Lakhāna, ṣāhi Mehama, ṣāhi Javūkha and devaṣāhi Khiṅgila.4

Scholars have pointed out that there is a continuity to the organisation of the political power in the Alchon kings situated in Gandhāra and Punjāb of India and the organisation of the polity into five yabghus who divided and ruled the land of the Yuezhi above the Amu Daryā and were later united by Kujula Kadphises in the first century CE in the form of the Kuṣāṇa Kingdom (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X, 280).

Figure 2 – Common Coinage of Four Alkhan Kings (Image Credit: Bakker, The Alkhan… 2020; 20)

Bakker points out that that interestingly in the scroll, the titles of the princes are aggrandized – from a rājā and a ṣāhi of the numismatics; they are now a mahārāja and a mahāṣāhi. Earlier, in the coinage, Khiṅgila was styled devarāja but in the scroll, Toramāna has taken up this Indianized title (Bakker, 2020; 26). Bakker attributed this change to the gradual increasing power of these Alkhan princes and particularly – Toramāna (Bakker, 2020; 26). This suggests that while earlier the foremost position in the quadrumvirate was that of Khiṅgila, the mantle later passed on to Toramāna by the last decade of the fifth century CE (Bakker, 2020; 26).

The stūpa this scroll was written for was founded in a place called Śārdīysa which according to Bakker was also the home town of queen Buddha who also was a daughter of King of Sārad [sārad ṣāhi](Bakker, 2020; 27). Bakker identifies this place with the present day village of Śārdi in the upper valley of the Kishangangā in Kaśmīra (Neelum valley, Pākistān Occupied Kashmīr) which we know as the seat of the goddess Śāradā (Śrī Śāradā Devī) and it seems that this valley was under the rule of Alkhan king Mehama.5 Bakker states that based on the available evidence it would be suffice to say that the Alkhan power was divided the north-west of the Indian subcontinent between the four potentates – Khiṅgila and Toramāṇa had Gāndhāra and Punjāb while Mehama and Javūkha had parts of Kaśmīra valley and Swāt respectively (Bakker, 2020; 27).

These rulers were supported by many local princes who also governed as feudatories and interestingly included the descendants of Kuṣāṇa-s, the Devaputra King of Tālagāna, the donor mentioned in the scroll (Bakker, 2020; 27). From the evidence of the scroll, Bakker concludes that the Alkhan rulers had entrenched themselves in the local centres of power through matrimonial alliances and were now evidently part of the Indic culture with particular interests in Buddhism at this point (Bakker, 2020; 27). Also a significant point to remember is that they were not alone; Hephthalite Huns were now commanding regions north of the Hindu Kush, particularly after they had defeated the Sāsānian Emperor Pērōz in 484 CE. Therefore, a long stretch of land was under the Hunnic tribes by this time.

§ Khurā Stone Inscription of Toramāṇa

Found from Punjāb (Salt Range, Pākistān), this inscription belonging to period quite close to the Schøyen Copper Scroll is a crucial source that clearly ascertains the ascendance of Toramāna in the confederation of the Alkhan-s. Just like the scroll, it is also concerned with a Buddhist foundation. According to the study of numismatics, it is safe to say that Devaṣāhi Khiṅgila was the senior one of the quadrumvirate and then we notice in the the Schøyen Copper Scroll that Toramāṇa had taken that title.6 Thus a hierarchy was already emerging and then we see the developments in the Khurā inscription in which Toramāṇa assumes multiple titles – Mahārāja, Rājādhirāja, Ṣāhi and Jaūẖkha, a curious combination of the Indian royal titles and the Central Asian ones (Bakker, 2020; 26).

The use of such grandiose titles also has another bearing which Bakker mentions through the suggestion of Harry Falk – “this may indicate that Toramāṇa saw himself as the founder of a dynasty (Bakker, 2020; 60).” Aspirations of something more than being a part of a confederation seems to be taking shape. The titles used in this inscription are also significant because they signal that a clear leadership among the Hunnic people in India was coming to the fore. The problem is that the date mentioned in the inscription has been lost but Bakker does suggest a date with his analysis. As we do see a development towards leadership in this inscription and this coupled with the fact that it is very close to the Schøyen Copper Scroll as far as paleography is concerned, Bakker dates (Bakker, 2020; 26) this somewhere around a year later than the Schøyen Copper Scroll which belongs to 495/96 CE, therefore, this inscription can be dated to ~ 497 CE.

Evidently, the quadrumvirate—known from the silver bowl, the common coinage, and the copper scroll—had been superseded at the time of the Khurā inscription.

Hans T. Bakker, The Alkhan: A Hunnic People in South Asia, 2020.

§ The Purāṇa-s

About the Hūṇa-s, some Indian sources also help us to confirm what the numismatics and other physical evidences like the copper scroll has informed us about their location. The 5th-century religious text – Viṣṇupurāṇa locates Hūṇa-s between the Sauvīra-s of Sindh and the Sālva living in Śākala (Siālkot in west Punjāb i.e. Pākistāni Punjāb) (Bakker, 2020; 38). Bakker points out that by this time the Hūṇa-s had been acknowledged to be living in part of the Indian world i.e. in its north, for example, a reconstructed old Purāṇic text called the Bhuvanavinyāsa or Das Purāṇa vom Weltgebäude mentions Hūṇa-s along with the Kāśmīra-s and Cūlika-s as living in the north (Bakker, 2020; 39).

§ The Rājataraṅgiṇī

The chronology of the Hūṇa rulers in Rājataraṅgiṇī of Kalhaṇa is very confusing.7 Especially the rulers concerning with the period of our study – Khiṅgila, Toramāṇa etc have been put after the period of Mihirakula, who we know was the son and successor of Toramāṇa. There is also a possibility that (in some cases) there have been other later rulers with these names but the fact remains that there is a lot of uncertainty with regard to the description of the Hūṇa rulers in this text. There is even the case of telescoping i.e. king with the same name is given the stories of an earlier king (Dezső & Hidas, 2020; X.1 296-297). Some have also tried to ascribe the Gardez Bhagavān Gaṇeśa statue to Khiṅgila, the senior of the quadrumvirate but in all likelihood, it belongs to one later Hūṇa ruler (Alchon-Nezak) of the same name in Kaśmīra.

§ The Headquarters of Toramāṇa

As to the location of the headquarters of Toramāṇa in the west Punjāb, the evidence is lacking except a very interesting hint in a rather ‘unexpected source’ – a late 8th century Jain Prākṛta text called the Kuvalayamālā by Uddyotanasūri (Bakker, 2020; 60-61). Bakker mentions the relevant text:

“On the banks of that (Chandrabhāya River) is the famous Pavvaïyā, decorated with precious stones, where the illustrious King Tora resided while ruling the earth. His guru was the venerable Harigupta of the Gupta lineage. At the time he accommodated him in that city (nayarī).” (Bakker, 2020; 61; see also Majumdar, 1970; 35).

According to the interpretation of the scholar, the residence Pavvaïyā of Tora, who could be identified with Toramāṇa can be deduced to the Jammu district, situated in the foothills of the Himālaya where the Chenāb (Candrabhāgā / Chandrabhāya River) Valley ends in the fertile plains of the Punjāb (Bakker, 2020; 62). The famous Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang) had also stated that the fortified town of Śākala (Siālkot in Punjāb, Pākistān) was once the capital of Mihirakula (Mihirakula, son of Toramāṇa) in the kingdom of Zhejia (Ṭakkā).8 But he also pointed out without giving us a name that the actual capital of the Zhejia kingdom was about 14 to 15 li north-east of Śākala (Bakker, 2020; 62). Now Bakker concludes (granting some inaccuracies in the distance) that this capital could be the town of Akhnūr tehsil in Jammu district (Bakker, 2020; 63-66) where excavations conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India in a site called Pambarwān had unearthed four layers of continuous occupation from pre-Kuṣāṇa to post-Gupta times (2nd century BCE-7th century CE) (Bakker, 2020; 66) and there were also found large amount of Buddhist remains along with some interesting coinage of the Kuṣāṇa-s and also one copper coin of Toramāṇa (Bakker, 2020; 66).

That this could have been an optimal and strategic situation for headquarters of the Hūṇa-s can be supported by the later presence of an 18th century Akhnūr Fort.9 Thus, the regions north of the Salt Range and west of the Jhelum River in west Punjāb were strongholds of the Hūṇa power in the early 6th century (Bakker, 2020; 51, 60) and these regions along with its adjoining areas seem to have formed the core of the kingdom of Toramāṇa at the turn of the sixth century from where he was effectively ruling over the confederacy that had Gāndhāra, Punjāb, parts of Kaśmīra valley and Swāt within their rule with his headquarters probably in Akhnūr.

India on the Eve of the Invasion

The flourishing empire of the Gupta-s, after reigning India for almost two centuries, was going through a rough patch post the end of the rule of Skandagupta. The internal struggles of the dynasty were affecting the external situation of the empire. Within nine years after Skandagupta, two Gupta emperors had sat on the throne of India – Purugupta, son of Kumāragupta I and his chief queen Anantadevī (r. 467-473 CE)10 and Kumāragupta II (r. 473-476 CE). However, respite came with the rule of Emperor Budhagupta, son of Purugupta and his chief queen Chandradevī (Majumdar, 1970; 30) who ascended the throne in 476 CE and provided the much needed stability for almost two decades. He established a firm rule and restored peace and order throughout the empire (Majumdar, 1970; 30).

But as Majumdar points out, there still were ominous signs of decline in the power and authority of the empire, especially in the outlying provinces – governors were becoming feudal chiefs, sometimes with the actual approval of the emperor (for example in case of Maitraka-s of Vallabhī) and feudal chiefs were well on their way to becoming independent kingdoms – the successor states of the Gupta-s, as some scholars call them (Majumdar, 1970; 30). Though sovereignty of the Gupta Emperor was still accepted “…as far as Bay of Bengal in the east, the Arabian Sea in the west and river Narmadā in the south”11 but with passing of time, it was becoming nominal in some places and outright absent in few of them (Majumdar, 1970; 31). A Mandasaur Inscription mentions in a rather vague manner the troubling times and rule of many kings between 436-472 CE (Majumdar, 1970; 32) suggesting troubling sitution in the western regions of the empire. Vākāṭaka King Narendra-sena apparently established his authority over the lord of the Mekala, Kosala and Mālava (Majumdar, 1970; 32). According to Majumdar, this implies an invasion of the Gupta territory from the south and this might have been the primary reason for decline in the Gupta supremacy in Bundelkhand and Baghelkhand (Majumdar, 1970; 32).

But the problems for the Gupta-s were to increase as Toramāṇa was deciding on his move in the ending years of fifth century. And who exactly was the Gupta monarch when the Hūṇa ruler was planning an invasion? Here the chronology after Budhagupta has created a lot of confusion and there still are many unanswered questions. Majumdar states that the official chronology of the Gupta-s mentions Narsiṁhagupta, another son of Purugupta after Buddhagupta (Majumdar, 1970; 33). Thus it would mean that Narsiṁhagupta ruled between 496/99 CE and 530 CE after which we have evidence for the rule of his son Kumāragupta III.

However, we have other contradictory information on this. We also know of another Gupta ruler named Vainyagupta from his Nālandā seal and his Guṇaighar (Comilla district, Bānglādesh) copper-plate grant of Gupta Era 188 (CE 506-07). Interestingly, new research has recently emerged regarding this mysterious figure of Vainyagupta. Scholar D. P. Dubey from Allāhabād University published his paper in which he deciphered new epigraphic evidence – a Raktamāla Copper-plate Grant dated to Gupta Era 180. The copperplate comes from a village near Mahāsthān, Bogrā District in the current Bānglādesh. It is written in Eastern variety of the Northern Brāhmi script in Sanskṛit and has the following legend –

si(śrī)paramabhaṭṭā[ra]kavainyaguptama(t-ā)dhi.12

As it is dated to year 180 of Gupta Era, the date of the grant is 499-500 CE (Dubey & Acharya, 2014; 3). Curiously, this inscription, probably the only one of its kind, also refers to deterioration in administration (apaśāsana) in the time of Gupta king in the empire, particularly, in north Bengal (modern Bangladesh) from Gupta Era 157 onwards which refers to 477 CE. The Gupta Emperor at this time was Budhagupta and thus augments the argument that the empire had started to deteriorate by this time, though it does seem like in other aspects of administration, Budhagupta took his time to streamline the affairs that had been disturbed due to weak rule of Purugupta and Kumāragupta II (Dubey & Acharya, 2014; 3). This new copper plate grant brings Vainyagupta in direct succession after Budhagupta. To understand more on this convulated situation – we also have the Nālandā Clay Seals of Kumāragupta III which in stating the genealogical list of the Gupta-s, completely by-passes Buddhagupta and Vainyagupta, the other sons of Purugupta and most likely brothers or half brothers of Narsiṁagupta. Incidentally another name is missing from the list – Skandagupta who was half-brother of Purugupta.13 The same omissions are repeated in Bhītari Copper Silver Seal of Kumāragupta III.14 Though, absence of some ruler in the genealogical lists of another ruler of the dynasty is argumentum ex silentio at best and it may mean several things, bad blood might not necessarily be one of them but here the events that followed clearly suggest that there was a rivalry – between Skandagupta and Purugupta at first and between the many sons of Purugupta later.

In such case, to make a coherent narrative we can guess a few scenarios. One, where Budhagupta dies in 496 CE and the throne is then claimed by Narsiṁagupta and Vainyagupta. As the majority of epigraphic evidence of Vainyagupta comes from Bengal, it seems like he claimed himself emperor (paramabhaṭṭāraka) in 499-500 CE – a fact that we now know from the Raktamāla Copperplate Grant but ruled mostly from the Bengal dominions of the Gupta-s which probably was his stronghold. Narsiṁagupta during his rule was either held captive by Vainyagupta or was not allowed to stay in the directly ruled regions of the empire, or some other reason because of which he was unable to held power. The sources that we possess till now state that the last known confirmed date for Vainyagupta is 506-507 CE (Guṇaighar Copperplate Grant). For how many years after this date did Vainyagupta rule or this was the last of his reign is uncertain as of now. Second scenario could be where Narsiṁagupta does proclaims himself emperor and rules from Magadha but Vainyagupta rebels, contests the throne and ends up proclaiming himself emperor, ruling from Gauda-Vanga.

One thing however is common to every scenario – unfortunately in this crucial period, the Gupta-s were a house divided, a fact which is unlikely to have gone unnoticed by the Hūṇa-s. They were not a confederacy anymore and had a leader in Toramāṇa. For long they have had north-west India in their sphere of influence and in this duration had gradually became part of the Indic world with special leanings towards Buddhism as proved by the Schøyen Copper Scroll and the Khurā inscription. External conditions were also favouring them as the Sāsānian Empire was also in trouble due to the coup against Kawād in 496 CE and despite his return to power in 498, the King of kings was entirely at the mercy of the Hephthal, the Hunnic rulers north of the Hindu Kush.15 Aspirations and ambitions were running high and at stake was the throne of India.

Archaeological & Literary Sources of the Indo-Hunnic War

§ The Eraṇ Stone Pillar Inscription

Eraṇ (Airikiṇa), an ancient town on southern banks of the Binā River in Madhya Pradesh is very significant due to its rich archaeological and historical finds and is an important source for the topic at hand. The Eraṇ stone pillar inscription of two brothers – Mātṛviṣṇu and Dhānyaviṣṇu, dated 484-485 CE is important for our study. This inscription is found on a Garuḍa column raised in honour of Janārdana and pertains to the building of a new religious complex for Bhagavān Viṣṇu. It mentions the Gupta ruler Budhagupta (r. 476-495 CE) as the sovereign (bhūpati) though rather nominally in the opinion of Bakker and a new power mentioned is one Mahārāja Suraśmicandra, told to be governing the land between the rivers Yamunā and Narmadā i.e. the western regions of the Gupta Empire. These brothers were to face the Hūṇa-s under Toramāṇa in a battle 12-13 years later.

Figure 3 – Watercolour Drawing by Frederick Charles Maisey of the Pillar at Eraṇ

§ The Eraṇ Boar (Varāha) Inscription

This is an extremely important inscription from the same religious complex and it is dated to the first year of the rule of Mahārājādhirāja Toramāṇa (Bakker, 2020; 28). The inscription was made by Dhānyaviṣṇu, younger brother of Mātṛviṣṇu, who now pledged allegiance to the Hūṇa ruler. The temple complex of the previous inscription evidently remained incomplete and Dhānyaviṣṇu obtained permission to complete this Vaiṣṇava temple complex by building a sanctuary, dedicated to Varāha, the boar avatāra of Bhagvān Viṣṇu (Bakker, 2020; 28). Based on the fact that in both the Schøyen Copper Scroll and the Khurā Stone Inscription, Toramāṇa has been called a Rājādhirāja, Bakker suggests the date of the Eraṇ Varāha Inscription to ~ 498 CE. According to him –

“This ‘first year’ cannot be much later than the Schøyen Copper Scroll and the Khurā Stone Inscription in which Toramāṇa used the title Rājādhirāja. A date around AD 498 therefore seems to be most plausible.”16

Figure 4 – A colossal statue of Varāha (Boar avatāra of Bhagavān Viṣṇu) in Eraṇ, Madhya Pradesh. (Image Credit: worldhistory.org)

§ The Sañjeli Copperplates

The three Sañjeli copperplates from North Gujrāta mention Toramāṇa as the supreme lord (mahārājādhirāja) (Bakker, 2020; 80). They are dated to regnal years 3, 6, 19. But scholar Salomon believes that we should not assume that Toramāṇa remained in control of this region for long (Salomon, 1989; 29) because only first of these copper plates mention Toramāṇa by name, the rest only using paramabhaṭṭāraka (Salomon, 1989; 29) which according to him increases the possibility that Toramāṇa actually ruled there for only six years (Salomon, 1989; 29). This however is only a suggestion and this particular evidence can be interpreted in a different manner which will be discussed shortly.

The copper-plate also mentions one Mahārāja Bhūta who was appointed by Toramāṇa as the district governor of Śivabhāgapura. The plates mention Vadrapāli which is identified with Sañjeli in Gujarāt and it was thus a town in the district of Śivabhāgapura. Vadrapāli was an important trade centre and it was part of the West Indian trade route. Additionally, these plates also offer evidence for the support of yet another Vaiṣṇava temple by Toramāṇa – the Temple of Jayasvāmin, Lord of Victory17 which was erected by the mother of Mahārāja Bhūta in Vadrapāli and was to be additionally maintained from the donation given by merchants of a twentieth (viṃśopakīnaka) on various commodities. The various places from which these merchants came also were part of the western trade route (Bakker, 2020; 80).

§ The Eraṇ Stone Pillar Inscription of Goparāja

This inscription from Eraṇ mentions the year 191 which scholars consider referring to the Gupta Era i.e. 510 CE. Bakker interprets inscription on the basis of the Fleet’s version of translation that says:

“There is the glorious Bhānugupta, the bravest man on earth, a mighty king, equal to Pārtha [i.e. Arjuna], exceedingly heroic; and Goparāja following [his] friend, came here along with him. And having fought a very famous battle, he [i.e. Goparāja], who was equal to the celestial king [i.e. Indra], [died and] went to heaven and [his] devoted, attached, beloved, and beauteous wife, in close companionship, accompanied [him] onto the funeral pyre.18

What exactly was the result of this battle is not certain. Some scholars interpreted the name of the king mentioned – Bhānugupta as a lesser known Gupta emperor but the relation of Bhānugupta with the imperial royal family is unclear and he may have belonged to the Gupta nobility of Daśārṇa (Bakker, 2014; 32) or could have belonged to the local elite of Vidiśā, the once western capital of the empire (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 339). Bakker also mentions on the suggestion of Dániel Balogh that Goparāja might have been the king of Gopa-giri i.e. Gwālior where later Mihirakula had a garrison stationed (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 339).

In a revised publication of ‘Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Volume III: Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings’ (1981), a different interpretation of the Goparāja inscription was presented. While in it the authors do accept that Bhānugupta may not have been a sovereign, he was “at least a contemporary scion of the Gupta family.19 They interpret the inscription as saying that Goparāja, chieftain or noble of Bhānugupta, came in his company to Eran and fought a battle with the ‘Maitras’ – this is the main change. In their translation they clarify the following lines – “…And along with him [Bhānugupta] Goparāja, following (him) without fear, having overtaken the Maittras and having fought a very big and famous battle, went to heaven, becoming equal to Indra..”20 But it is an inconclusive interpretation because they also accepted that the name Maittras is neither quite clear nor beyond all doubt but they still conclude that it is as good as certain.21 However, the enemy in the battle that was fought (yuddham sumahatprakāśam) does seems to have been Toramāṇa (Bakker, 2014; 32) as Bakker believes that in light of what follows, it appears that the battle being alluded to in the inscription might have been against the Hūṇa.

§ The Rīsthal Inscription of Prakāśadharman

This crucial inscription confirms that the later-Aulikar ruler Prakāśadharman was responsible for defeating Toramāṇa. The king has been praised in eloquent words in this inscription found near Mandasaur (Daśapura) and belongs to the year 515 CE. Of this illustrious king, the inscription says –

“By whom the title ‘Overlord’ (adhirāja) of the Hūṇa commander (adhipa) was nullified in battle, (though it) had been firmly established on earth by the time of King Toramāṇa, whose footstool had glittered with the sparkling jewels in the crowns of kings (that had bowed at his feet) (Bakker, 2020; 90).”

§ The Sack of Kauśāmbī

We learn from the excavations conducted at the ancient city of Kauśāmbī that the latest levels of occupation suffered what Bakker calls a “destruction on an unparalleled scale (Bakker, 2020; 77).” The excavations of the Buddhist Vihāra of Ghoṣitārāma in Kauśāmbī revealed a seal impression of the monastery counter-marked with letters To Ra Ma Ṇa (Bakker, 2020; 77). The city never seemed to have recovered from this attack (Bakker, 2020; 77). Another scholar Pankaj Tandon is of the opinion that this Toramāṇa sealing at Kauśāmbī was made i.e. counter-marked right there rather than brought from elsewhere (Tandon, 2018; 260). The stratum in which the sealings of Toramāṇa and one with ‘hūṇarājā’ were found had evidence of large scale destruction and large quantities of a particular type of arrowhead not characteristic of other strata (Balogh, 363). These barbed arrowheads of Hun type found in excavations at Kauśāmbī, combined with the evidence of these sealing (also mentioned in a previous post on the blog) corroborates the presence of Huns in that city (Tandon, 2018; 260).

§ Numismatics

The Prakāśāditya Coin: A seminal study by Pankaj Tandon has shed new light on the coinage of Toramāṇa in the period that we are concerned with. This relates to confirming the identity of Prakāśāditya on some gold coins found. Ever since the discovery of the coins with this reading of Prakāśāditya on them in 1851 CE in the Bharsār Hoard near Vārāṇasī, it was assumed by almost all scholars that the coins must have belonged to the Gupta dynasty as these were mostly found along with those of the Gupta Emperors like Samudragupta and Skandagupta (Tandon, 2015; 647-648). Then Robert Göbl, the Austrian numismatist suggested in 1990 in his ‘Das Antlitz des Fremden: Der Hunnenkönig Prakasaditya in der Münzprägung der Guptadynastie (The Face of the Stranger: The Hun King Prakāśāditya in the Coinage of the Gupta Dynasty)’ that this king was not a Gupta, but a Hūṇa.22

The coins are horseman lion-slayer type and the figure on the obverse is, presumably a king, mounted on a horse right and thrusting his sword through the gaping mouth of a lion at right (Tandon, 2015; 648). There’s also the symbol of Garuḍa above the horse’s head and a prominent Brāhmi letter under the horse (Tandon, 2015; 648). The reverse has a goddess seated on a lotus, holding a diadem and a lotus along with a legend śrī prakāśāditya on the right (Tandon, 2015; 648).

The main problem for earlier scholars was to determine which Gupta king this belonged to because the obverse legend that typically revealed the ruler’s name remained unread (Tandon, 2015; 649), revealing only the last part that read viji(tya) vasudhāṁ divaṁ jayati (having conquered the earth, wins heaven). More troubling was the point that no epigraphic or literary source revealed a Gupta king with biruda prakāśāditya. And despite the similarity with the Gupta coinage, there were some significant differences. All of the Gupta coins that either have a horseman or a lion/tiger slaying type, also have one common similarity – the ruler is always shown standing on the ground and never riding a horse and slaying the lion or tiger, unlike the case with Prakāśāditya coins,23 though there are Gupta coins that depict riding a horse or elephant and slaying a rhinoceros/lion respectively but this was a completely new innovation which Tandon says was unlikely for a minor king (Tandon, 2015; 650). Also important is the fact, accepted by many scholars that the coins evidently lacked the grace of the Gupta art.

These coins were then identified with various Gupta emperors in the course of time since their discovery – Purugupta,24 Budhagupta,25 Tathāgatagupta,26 Bhānugupta,27 with Prakārākhya, son of Bhakārākhya (this is the version of the names that scholar P. L. Gupta had used in his analysis of MMK; they correspond with Prakaṭāditya, son of Bhānugupta as per Jayaswal’s interpretation) (Tandon, 2015; 654-655), even with Yaśodharman.28 However, all of these identifications were inconclusive and sometimes based on mere speculations.

But Tandon conclusively read the legend as avanipatitoramā(ṇo) viji(tya) vasudhāṁ divaṁ jayati (the lord of the earth Toramāṇa, having conquered the earth, wins heaven) in Upagīti meter (Tandon, 2015; 663-666). There are also very distinct Hunnic features on these Prakāśāditya coins [notice the elongated head, characteristic of the Hunnic tribes], some of which also seem to be inspired from the Sāsānians as noted by Göbl and confirmed by Tandon (Tandon, 2015; 657-659). Also the presence of the symbol of Garuḍa in fact points towards these coins being a non-Gupta manufacture (Tandon, 2015; 660); a “departure from the Gupta practice” as the horseman type or the lion-slaying type Gupta coinage never had this symbol (Tandon, 2015; 14; also see Bakker, 79).

Figure 5 – A Comparison of the silver plate of the Sasanian king Wahrām V hunting lions with the Prakāśāditya Coin of Toramāṇa. This was likely inspiration for the Hūṇa ruler along with the Gupta coinage. (Image Credit: Bakker, The Alkhan.. 2020; 85, 78)

Fascinating point to note about these Prakāśāditya coins is that the Alkhan symbol (tamgā) is conspicuous by its absence (Bakker, 2020; 78). Significantly, there were also found many copper coins of clearly Hun origin that had legend śrī prakāśāditya, śrī udayāditya and śrī vaysāra (Tandon, 2015; 656) and they were no doubt inspired from the Gupta copper coins. And we also have example of Toramāṇa copying silver coin from a Skandagupta prototype (Bakker, 2020; 78). Toramāṇa issued these silver coins based on the Gutpa madhyadeśa type (Tandon, 2018; 257) and these were also much cruder and were generally found in Mālwā, where they were struck (Tandon, 2018; 257). So, it makes sense that since Toramāṇa issued silver and copper coins in imitation of the Gupta-s, that he would then certainly try to do so with the gold ones (Tandon, 2018; 258).

The ‘Nameless’ Archer-Type Coins: Another kinds of coins pertaining to our topic are the ‘Nameless’ Archer-Type coins. Regarding this, important research has been published by Tandon in which he attributes these coins to the Huns and not the Gupta-s as has been previously considered (Tandon, 2018; 257). Another pertinent feature of the provenance of these ‘Nameless’ Archer-Type coins is that these are found almost exclusively in eastern Uttar Pradesh (Tandon, 2018; 260).

§ Ārya Mañjuśrī Mula Kalpa

This important Mahāyāna Buddhist text is in Sanskṛit and narrates important historical events of India till the 8th century CE. The text was later also translated in Tibetan in 11th century. Scholar K. P. Jayaswal had analysed this text and gave his interpretation. It mentions a king named P. (Pra. in Tibetan) and was son of Bh. and is a contemporary of king Gopa who does not belong to the dynasty (Jayaswal, 1934; 53). The text says –

“Pra was a bad boy of the family and had been imprisoned up to the age of 17. He was brought out of prison by an invader who was very powerful and had reached the East, having come from the West. He enjoyed kingdoms acquired by others. He crowned the young Pra. as king of Magadha at Benaras, and then after a bout of illness died on his march (Jayaswal, 1934; 53).”

Jayaswal interpreted that Pra. or P. here stands for Prakaṭāditya [which is known from an inscription on a pedestal form Sāranātha (Tandon, 2015; 655)] and Bh. for Bhānugupta who is mentioned in the Eraṇ inscription whose subordinate Goparāja fought in the battlefield and lost his life. And the H. here stands for Toramāṇa, the Hūṇa (Jayaswal, 1934; 53) who is described as a great king (mahānṛpaḥ) with large and powerful army.29 Jayaswal’s analysis suggest that the Hūṇa-s had reached up to Magadha, gone to a town called Bhagavatpura and here they caught hold of Pra. and set him up as the king of Magadha (Jayaswal, 1934; 54). It also suggests that though Pra. was installed at Benaras, he actually became the king only after the death of the Planet (Planet or Graha, the son of H. has been interpreted by Jayaswal to refer to Mihirakula as Mihira [sun] could be meant here).

Adding to this, the text clarifies that imprisonment and release of Pra. happened while Bh. was alive (Jayaswal, 1934; 54). Based on the testimony of Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang), according to whom Magadha was subject to Mihirakula but the ruler of Magadha, Bālāditya rebelled and later defeated Mihirakula (Jayaswal, 1934; 54), Jayaswal thus concluded that Bhānugupta’s āditya name was Bālāditya and was the father of Pra. i.e Prakaṭāditya. He then concludes that Bhānugupta Bālāditya retired to Bengal under pressure from the Hūṇa-s (Jayaswal, 1934; 56) in or following 510 CE. Prakaṭāditya was therefore the one who was freed and made the king at Nandanagara (Pāṭaliputra) but before anything could be made permanent, Toramāṇa dies at Benares.

However, we need to keep this in mind that when Jayaswal wrote his interpretation of Ārya Mañjuśrī Mula Kalpa, Narsiṁhagupta’s identity was still unknown. But since then, it is confirmed that Narsiṁhagupta was the one with the biruda of Bālāditya and he (along with Vainyagupta) succeeded Budhagupta, and it was he who was one of the Indian powers who defeated Mihirakula, son and successor of Toramāṇa. Add to this the fact that until now since Jayaswal wrote his analysis, Bhānugupta is still an elusive figure about whom we still do not know anything more than what we did decades back. Some scholars, as mentioned above had tried tie the identity of Bhānugupta with the Prakāśāditya coins but as we just discussed, those coins are conclusively proved by Tandon to belong to Toramāṇa instead. Therefore, while this text is important as it mentions some hitherto unknown information; some of which is also corroborated by physical evidence but at the same time there is some contradiction in the text and therefore, we need to be careful while basing history on this alone.

The Later or Imperial Aulikara-s & the Naigama Family

As just discussed above, Toramāṇa was defeated by the later Aulikara ruler Prakāśadharman. But who was this Prakāśadharman and who were the later Aulikara-s. Prakāśadharman was the predecessor of the famous later Aulikara ruler Yaśodharman, whom we know of from his inscriptions to have defeated Mihirakula and expelled the Hūṇa rulers from mainland India. For a long time, it was considered that Yaśodharman rose out of nowhere ‘like a meteor’ and faded just as fast. But from what we will learn in brief in the following sections, it becomes more and more clear that he was very much part of the political environment and his rise was actually a result of the rise of the later Aulikara-s presumably under his predecessor and father Prakāśadharman, who rose against foreign invasions that too at a time when the imperial Gupta-s were unable to.

§ The Aulikara-s

The history of this illustrious dynasty of Aulikara-s, though extremely fascinating, is out of the purview of this topic and deserves its own separate study, something I hope to do in future. For the current study, it suffices to say that the Early Aulikara-s (not to be confused with the later Aulikara-s) can be traced ruling in and around the region of western Mālwā i.e. the area of Daśapura (Mandasaur), though there is some trace of their ancestry in Daśārṇa i.e. eastern Mālwā as well (Balogh, 20-21;23).

Some scholars have tried to paint the Aulikara-s as quite independent of the Gupta-s. However, Salomon provides good argument against this. Early Aulikara ruler Prabhākara of late fifth century has been described as “the fire to the trees of the enemies of the Gupta line” — a statement which according to him suggests quite clearly that they were subordinates to the Gupta-s (Salomon, 1989; 26). The nature of their alliance, according to Salomon may have been somewhat like that of the Vākāṭakas who maintained a quasi-independent status, guaranteed by marital connection in alliance with the Guptas (Salomon, 1989; 26).

There is thus a possibility that later Aulikara line began as feudatories or subordinates of the Gupta-s but gradually became independent (Salomon, 1989; 26). Salomon emphasizes his point by quoting S. R. Goyal —

“The rulers of this family enjoyed considerable freedom in the administration of their state, though there is hardly any reason to doubt their subordination to the Gupta Emperor.”

S. R. Goyal, year, as cited in Richard Salomon, 1989.

There is no certainty that the Early Aulikara-s whose inscriptions trace their predecessors to ~ 380 CE were directly related to Later or Great Aulikara-s though future excavations may unearth some new inscriptions or some new evidence can help us understand their connection. As of now, it appears that they were not direct descendants but it is not improbable as well (Balogh, 2019; 29). The Later-Aulikara inscriptions mention at least five predecessors of Prakāśadharman going back to ~ 420 CE30 who could have been local rulers or subordinate governors during the prime of Early Aulikara-s (Balogh, 2019; 29). Though Prakāśadharman was probably not as powerful as his successor, he was nonetheless a figure of considerable stature (Salomon, 1989; 12).

Interestingly, we have another important possibility: Between the Early Aulikara-s and the Later Aulikara-s, Daśapura seems to have been ruled by a family of Māṇayavāyaṇis (Bakker, 2020; 81), and we have two inscriptions of a Mahāraja Gauri of this dynasty – the Choṭī Sādrī Inscription (491 CE) and Mandasor Fragmentary Inscription (Bakker, 2020; 80). Though themselves they are not very important for the topic of this current post but the Mandasor Inscription of Gauri after its dedication to Bhagavān Viṣṇu mentions one King Ādityavardhana who is said to rule the town of Daśapura after having slain his enemy in the battle (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 332). Though the name is ending with ‘vardhana’ and as Bakker points out, various rulers ending with this name have been known to rule this region in fifth and sixth centuries but scholars are unable to link this king positively with any of those lineages (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 332). Only one ruler of Mālwā in the last decade of fifth century is known — Toramāṇa.

Bakker also thinks that the name could be a connection where the use of Āditya was again seen in the gold coin of Toramāṇa which he got minted by imitating the Gupta-s – the legend on them was Prakāśāditya. The dedication to Viṣṇu – Rider of Garutmat also reminds us of the Garuḍadhvaja on the dinārs that he copied from the Gupta-s (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 332-333). So, there is a possibility that King Ādityavardhana is actually Toramāṇa and if not him, then a figurehead installed by him and that is why between the Choṭī Sādrī Inscription (491 CE) and Mandasor Fragmentary Inscription, Daśapura had been conquered, and we do not see Gauri using Mālava Era anymore. 31

§ The Naigama-s

The Naigama family or “dynasty of Naigamas” (anvavāyo … naigamānām) (Balogh, 2019; 30) as it has been called in the inscriptions provided hereditary chancellors (rājasthānīya) to the Later Aulikara-s royal family (Balogh, 2019; 30). Various inscriptions like the Mandasaur Stone Inscription of Nirdoṣa, the Rīsthal inscription mention them and the Chittorgarh inscriptional fragments (Balogh, 2019; 30) also provide information about them. Their family relations are not very clear but the fact that several generations of them served as chancellors to the later Aulikara-s is certain (Balogh, 2019; 30). As stated before, I do not want to go into details in this post as I hope to do a separate one on them and their connection with the later Aulikara-s in future on this blog but I would like to mention some interesting points nonetheless. The term ‘rājasthānīya’ implying the office of rājasthānīya has been mentioned many times in the epigraphic records, though the exact meaning and functions of this office are not known clearly (Balogh, 2019; 8). Some scholars consider them as viceroys or regents but Balogh chooses to use chancellor instead because –

“The rājasthānīyas of the Aulikaras evidently functioned side by side with a king in full possession of his faculties, so neither of these translations is appropriate (Balogh, 2019; 8).”

§ The Connection between the later Aulikara-s, the Naigama-s and the Gupta-s

The family foundation of the Naigama-s goes back to ~ 460 CE (Balogh, 2019; 98) and their founder took refuge under Yaśodharman’s ancestors and by the time of Prakāśadharman, the grandson or great grandson of this family – Doṣa/Bhagavaddoṣa was the chancellor for the House of Later Aulikara-s (Balogh, 2019; 30) and was succeeded by brother Abhayadatta and then son Dharmadoṣa. This family most likely started as merchants and as per an interesting suggestion of Balogh they could even be descendants of the silk weavers of the Mandasaur Inscription who moved from Lāṭa to Daśapura and took to various other occupations (Balogh, 2019; 30) and they could also have been part of the guild of these silk weavers (Balogh, 2019; 97). Balogh even hints at an alliance between the guild of the silk weavers and Early Aulikara-s with mutual benefits and a similar alliance was then made by the Naigama-s (if we entertain the suggestion of them being descendants of the silk weavers) with the Later Aulikara-s.

“An alliance with a newly independent and successful group of political elites like the Aulikaras would certainly have elevated the social status of the Naigama family. The Aulikaras, too would have benefited from their ties to the prominent local merchant group, who may have helped them to control the surplus from trade and commerce in the area (Cecil, 2020; 63).”

One scion of this family named Ravikīrti had a wife named Bhānuguptā (both of whom are mentioned in the inscription of Yaśodharman) who bore him three sons and the first of these three sons – Doṣa (Bhagavaddoṣa) was the chancellor of the later Aulikar King Prakāśadharman (Balogh, 161). In fact, there are many other hints in this inscription which according to Balogh suggest that the later Aulikara-s also intermarried with the family of the Naigama-s (Balogh, 2019; 162). Interestingly, it is suggested that this Bhānuguptā might have been connected with the Gupta-s.

“Since the lady’s name was Bhānuguptā, it has been suggested…that she may have been related to King Bhānugupta, who was alive circa 511 CE (GE 191) according to the Eraṇ pillar inscription of Goparāja and who may in turn have been related to the imperial Guptas. However, the combined evidence of the Rīsthal inscription and the Mandsaur stone tells us that Bhānuguptā’s son Doṣa was a minister of Prakāśadharman in 515–516 CE, so if Bhānuguptā was indeed a relative of Bhānugupta, she must have been the older of the two (Balogh, 2019; 161).”

The Invasions – An Analysis

Through various archaeological findings, we now have confirmed dates and chronology of certain anchor points in the first Indo-Hunnic war during the time of Toramāṇa. The most primary date, according to Bakker is the Eraṇ Varāha Inscription which he ascribes to ~ 498 CE which was the first year of the reign of Mahārājādhirāja Toramāṇa. The next is first of the Sañjeli copperplates dated to his third year (~ 500-501 CE) and then we have the Eraṇ Stone Pillar Inscription of Goparāja-Bhānugupta dated to 510 CE. At last, we have the Rīsthal inscription of Prakāśadharman which belongs to 515 CE. To add to this, confirmed from the archaeological excavations, numismatics and corroborated by literary sources, we know that Toramāṇa reached the core regions of the Gupta Empire, at least up to eastern Uttar Pradesh. With these anchor dates and facts at hand, we now are faced with the task of understanding the detailed chronological possibilities of these.

§ The First Hunnic War Begins

What we know is that sometime in around ~ 497 CE, finding the timing opportune with the Hephthal Huns exercising influence over the Sāsānians as a strong external factor and the contested throne among the Gupta-s as a strong internal factor, Toramāṇa invaded north and western India from Punjāb (Bakker, 2020; 68), from his stronghold on the banks of Candrabhāgā River (Bakker, 2020; 68). He invaded the Antaravedī (Gaṅgā-Yamunā Doab) and conquered Mathurā (Bakker, 2020; 73). Toramāṇa then “crossed the Yamunā near Kalpi (Kālpriyanātha) and marched south into the Betwā Valley in order to attack the western territories of the Gupta Empire (Bakker, 2020; 73).” The First Hunnic War, a term suggested by Bakker, or the First Indo-Hunnic War had begun.

§ The First Battle of Eraṇ

The battle had gone bad for the Indians and certainly for Mātṛviṣṇu, the elder of the two brothers of the Eraṇ Stone Pillar Inscription, who probably lost his life in the battle. Dhanyaviṣṇu, the younger brother now had to choose between accepting the new lord or die and he chose the former (Bakker, 2020; 76). But he was allowed by Toramāṇa to complete the theriomorphic image of the Varāha (Bakker, 2020; 76). The sculpture and temple complex was allowed by the Hūṇa ruler to be completed and the inscription was etched on the sculpture in which Toramāṇa was now proclaimed as Mahārājādhirāja.

“Though rather isolated today, in classical times Eran (Airikiṇa) guarded the main passage from Mathurā, via Gwālior, through the valley of the Betwā to the rich province of Daśārṇa (Eastern Malwa) and its capital Vidiśā. And so it became a battlefield where invaders and local kings regularly clashed (Bakker, 2014; 31).”

What happened to Mahārāja Suraśmicandra who was mentioned in the Eraṇ Stone Pillar Inscription as governor of the land between the rivers Yamunā and Narmadā i.e. the western regions of the Gupta Empire? As evidence stands today, we do not know anything about him. His authority was clearly extensive, so much so that Emperor Budhagupta was acknowledged as the sovereign but in a lack luster language. Did he lose his life in the battle with Toramāṇa? Or was he not even the governor anymore. After all, twelve to thirteen years — a long time — had passed between the inscription in which he was mentioned and the one which was written after the battle of Eraṇ had been lost. Had someone else taken his place? Was that someone Bhānugupta?

According to scholars and historians Bhānugupta was a governor of the western headquarters of the Gupta-s or a local elite of Vidiśā and probably related to the imperial Gupta-s as well. Again, we do not know whether he was present at this time in the region or not. If he was present, did he take part in the battle as well? If he was not present and a battle with them did not take place, does that mean that the western Gupta forces i.e. forces of Bhānugupta were taken by surprise and did not have time to react? Unfortunately, there are too many unanswered questions in this story. Whatever was the case, either Toramāṇa did not have to face the forces of the western headquarters of the Gupta-s or if he did, he was able to overpower them because it does not seem possible that Toramāṇa would be able to assume kingship in the region without defeating or subjugating the governor of the Gupta forces of the western region. In either case, Toramāṇa was right in choosing the time that he chose to attack because the Gupta-s were unable to stop him at this point which in all likelihood was due to the uncertainty of the Gupta court. It seems that the Hūṇa ruler was now adhipati i.e. the lord of the lands between Yamunā and Narmadā rivers.

§ The Campaign in Gujarāt and Rājasthān

The next significant step that the Hūṇa ruler took was his capture of the major trade routes of western India (Bakker, 2020; 80). Without wasting much time, Toramāṇa now launched his campaign in his second or third year towards Gujarāt and Rājasthān (Bakker, 2020; 79). He went through Madhyamikā, (Nagarī / Chittor), Daśapura (Mandasaur), then to Bharukaccha (Bharūch) ending at the very important Gulf of Cambay (Bakker, 2020; 79).

He “seems to have followed the ancient caravan track from Mathurā to the Gulf of Cambay, cutting short the eastern route through the Betwā Valley followed in his first invasion (Bakker, 2020; 80).”

The western trade route in the control of the Hūṇa ruler meant that he could benefit from this and can now connect it with the Central Asian trade network which at the time was in the hands of his allies, the Hephthalite Huns north of the Hindu Kush (Bakker, 2020; 80). There’s no doubt that control over such vast and lucrative trade route must have been a big boost in the financial condition of the Alkhan-s.

However, his ride seems not to have been that smooth which this continuous trail of military victories suggests. Only the first of the Sañjeli copperplates mention Toramāṇa by name as a ruler in his third year of reign and his name is absent in the next two plates which belonging to years six and nineteen and the king is only mentioned with the title paramabhaṭṭāraka. As stated before in the post, according to Salomon, this suggests that his rule in northern Gujarāt was probably only six years (Salomon, 1989; 29).

Bakker however disagrees and thinks that the year 3 and 19 fit the chronology of what we know of trajectory of Toramāṇa32 which began with his ascendance in c. 495-496 CE (the Schøyen Copper Scroll and the Khurā Inscription) and ended with his defeat at the hands of Prakāśadharman in 515 CE. Add to this the fact that no other paramabhaṭṭāraka ruling Gujarāt and Rājasthān is known in this period. Why his name was then not included in the last two copperplates? Bakker suggests that it could be because these copperplates were known to have belonged together from the start and thus no need was felt to inscribe what was already included in the last one (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 337). Interestingly, the Sañjeli copperplates then also suggest that Toramāṇa who had earlier considered his reign to start from ~ 498 CE in Eraṇ as a mahārājādhirāja, now considered his reign to start from his ascendance, right when he got control of the quadrumvirate and made sure to get this date counted when his royal titles are mentioned in the Sañjeli copperplates as paramabhaṭṭāraka mahārājādhirāja śrī toramāṇe.

§ The Second Battle of Eraṇ

At this point, control over Mālwā was challenged because in 510 CE, Bhānugupta was fighting the Hūṇa ruler. However, one should not discount the involvement of Goparāja, who we know fell in the battle fighting the enemy. Goparāja, as we know from the inscription came from an illustrious royal family of this region, both from his father and his mother’s side (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 338). And as mentioned above may have been the king of Gopagiri – Gwālior (Bakker, 2020; Chap. X.2, 338). The language of the inscription suggests that he was also more of a peer of Bhānugupta, rather than a general serving his lord in the battle – ‘tenātha sārdhaṃ tv iha gopar(ājo), mitrānu(gatyena) kilānuyātaḥ’ – ‘and, Goparāja following his friend, came here along with him.’33

Another way the words had been used in the inscription suggest that this battle was an important one – ‘kṛvā [ca] (yu)ddhaṃ sumahatprak(ā)śaṃ’ i.e. ‘and having fought a very famous battle.’

But historian Majumdar is unsure whether this battle that took place in Eraṇ in c. 510-511 CE was an attempt to resist the advance of Toramāṇa or an endevour to drive him out of Eastern Mālwā which he had already conquered (Majumdar, 1960; 95). The former would mean that Bhānugupta had established control over Eastern Mālwā, probably when Toramāṇa was busy in his campaign in Gujarāt and Rājasthān and he was now trying to re-establish his authority. The latter would mean that this was a battle fought by Bhānugupta to finally wrest the region from Toramāṇa and drive out the invader. There is however, another possibility where ‘resisting the advance’ could mean that the battle was lost in the process of stopping Toramāṇa in his campaign/invasions in eastern regions of the Gupta Empire. Does that mean that the Gupta Emperor Vainyagupta (or Narsiṁhagupta?) had learnt of an impending invasion of Toramāṇa over the eastern regions of the empire and had authorised Bhānugupta to resist his advance? As evidence stands, there are many possibilities regarding the reason this battle took place. And unfortunately, we do not know what happened to Bhānugupta. Presumably he died in the battle and Toramāṇa successfully invaded the eastern regions.

§ A Concerted Effort?

Another interesting angle is suggested by Bakker who is of the opinion that Bhānugupta may have had the support of Prakāśadharman, the later Aulikara ruler in this battle against Toramāṇa since Bhānugupta’s sister (?) Bhānuguptā was married to Ravikīrti (Varāhadāsa?) who was a chancellor under Prakāśadharman’s father Rājyavardhana.34 And similarly, Ravikīrti’s son Bhagavaddoṣa (Doṣa), who also served as the chancellor of Prakāśadharman might have also fought on side of his maternal uncle (Bakker, 2014; 33). If we take this suggestion as a real possibility, then this means that the later Aulikara-s directly or indirectly, the Naigama-s, the Gupta-s (through Bhānugupta) along with the other local elite (through Goparāja) might have been involved in a concerted effort to stop the Hūṇa ruler, hence the famous battle – yuddhaṃ sumahatprakāśaṃ – was fought. This consequently could mean that entire Mālwā played an active and concerted role to stop Toramāṇa and that the last battle in which Prakāśadharman defeated him was also not a standalone attempt but one in continuation of the second battle of Eraṇ.

§ The Invasion of the Eastern Regions & Subjugation of the Gupta-s

Toramāṇa seems to have thought through his plan of the invasion of Indian mainland. His first move was the control of the lands between Yamunā and Narmadā and then he turned towards the western regions of Gujarāt and Rājasthān, effectively controlling the western trade route. This explains the numismatics – the silver and copper coins he minted in the Gupta style during his rule here. This gave him his financial source for a future invasion of the eastern regions which formed the core of the Gupta Empire at this point. It then seems that he advanced towards his goal in ~510 CE and in the process, he was resisted by the Indians, presumably led by Bhānugupta. As mentioned above, we cannot be sure whether Bhānugupta was authorized by the Gupta Emperor or not but the battle was lost and then Toramāṇa advanced further east.

It seems that there was resistance from the Indians, though we are not certain how much and for how long but what is certain is that the ancient city of Kauśāṁbī faced destruction on scale that was unparalleled. As previously mentioned, this is supported by archaeology – the sealings of Toramāṇa and one with ‘hūṇarājā’; the Hun type of barbed arrowhead not characteristic of other strata (Balogh, 363) – all support the fact that Kauśāṁbī was sacked. The evidence of the nameless archer type coins, as previously mentioned, found only till the region of eastern Utter Pradesh also supports that they were Hunnic issues and that the Hūṇa ruler had reached at least till Kauśāmbī and also probably Vārāṇasī because if they were Gupta issues, as Tandon points out, there would be no reason for them to not be found in Bihar (Tandon, 2018; 260).

During his course of invasion, Toramāṇa also issued his Prakāśāditya gold coins, clearly in imitation of the Gupta-s, but did some innovation with its details, putting the stamp of his own style on them. The Buddhist text Ārya Mañjuśrī Mula Kalpa, even though contradicting in some cases, nevertheless provided some interesting details and states that the Gupta-s were subjugated by the Hūṇa ruler who in all likelihood, according to scholars, was Toramāṇa. The rest of the details cannot be confirmed for now but as we just discussed, archaeology overwhelmingly supports that this was true. Keeping in mind the confirmed evidence that the Alkhan Hūṇa-s issued copper, silver, and gold coins roughly on the Gupta pattern, it also suggests that they must have a substantial and rich empire with capacity to issue a relatively large volume of gold coins (Tandon, 2015; 668).

“Toramāṇa was able to have his Prakāśāditya coins minted and issued proves his firm grip on important parts of the Gupta territories and administration (Bakker, 2020; 79).”

Probably Vainyagupta was the Gupta monarch who was overpowered and ran to Gauda or he actually was defeated and had to accept the overlordship of Toramāṇa and this humiliation probably gave Narsiṁhagupta the chance to now claim throne for himself. It is however also possible that Vainyagupta lost his life in the ongoing struggle and it was now up to Narsiṁhagupta to carry on the mantle. Probably this is the reason that there are no inscriptions of any kind belonging to Vainyagupta (his last known date we have is ~506-507 CE from the Guṇaighar Copperplates) after 510 CE.

It seems that Narsiṁhagupta Bālāditya was now the Gupta monarch and he, knowing that the empire had been devastated with these constant attacks and financial exactions or tributes that Toramāṇa might have decided upon, Narsiṁhagupta decided to buy his time and consolidate his power. At this point, the Hūṇa-s, jubilated with this humongous victory, presumably made their way back to the west but it seems that this was not the last. Prakāśadharman had made plans of his own.

The Victorious Prakāśadharman

The Rīsthal inscription quoted by Bakker gives us an insight into how devastating the battle might have been in which the Hūṇa ruler was defeated (Bakker, 2014; 34) –

“He [i.e. Prakāśadharman], who by battle rendered the title ‘Lord’ of the Hūṇa king false, (though it) had been firmly established on earth up to Toramāṇa, whose footstool had glittered with the sparkling jewels in the crowns of kings (that had bowed at his feet); By whom auspicious seats were offered to the ascetics, splendid ones, made of the long tusks of that same (king’s) elephants, whose rut was dripping (from their temples) while they were being shot down by (his) arrows at the battle front; And by whom were carried off a choice of ladies of the harem of that same (king), whom he had defeated by his vigour in the thick of battle, after which he offered them to Lord Vṛṣabhadhvaja (i.e. Śiva) to mark the strength of the arms of the ‘Light of the World’ (Lokaprakāśa, i.e. Prakāśadharman).”35

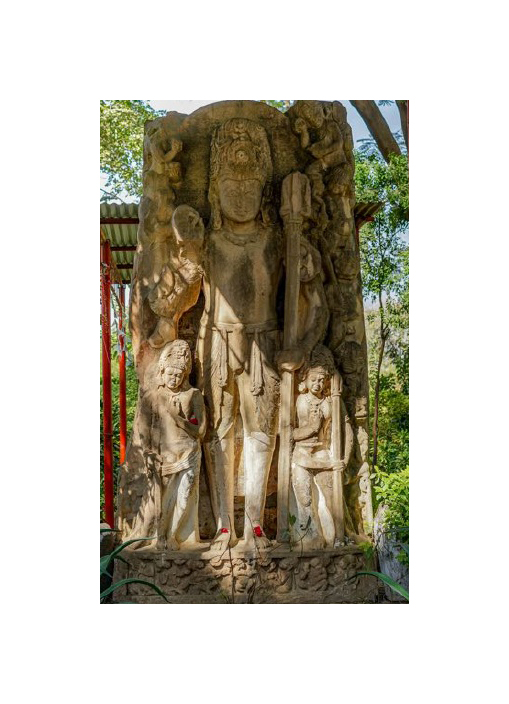

Figure 7 – Image of Prakāśeśvara (Bhagavān Śiva) after restauration, Mandasor Fort. It was found in the fort in 1908. (Image Credit: Bakker, The Alkhan.. 2020; 91)

Another translation of the relevant text is provided by Salomon –

“He falsified in battle the Hūṇa overlords title of “Emperor”, which (had) become established on earth up to (the time of) Toramāṇa, whose footstool was coloured by the rays of light from the jewels in the crowns of the kings. [16] He presented to holy ascetics beautiful (ivory) seats made from the long tusks of the rutting elephants of that same (Toramāṇa), which he brought down with his arrows at the forefront at the battle. [17] And he carried off and dedicated to Lord Vṛṣabhadhvaja (Śiva) the fairest ladies of the harem of the same (Toramāṇa) whom he had defeated easily in the thick of the battle, as token of the power of his arms which illuminate the world. [18]. (Salomon, 1989; 8)

Prakāśadharman had resoundingly defeated Toramāṇa and it is also corroborated by the archaeological findings that confirm the date for the start of the reign of his son and successor, Mihirakula – 515 CE. Important to note however, is that Toramāṇa was defeated but not killed and here the point from Ārya Mañjuśrī Mula Kalpa might be relevant which says that Toramāṇa fell ill, crowned his son the king and then died leaving Mihirakula to handle the situation. This means that the battle in which Prakāśadharman defeated Toramāṇa is likely to have happened in ~513-514 CE because the Rīsthal inscription of 515 CE was made to mark the dedication of a temple to Bhagavān Śiva and the construction of a water tank, events that according to Tandon, might have occurred well after the battle against Toramāṇa which possibly was Prakāśdharman’s greatest achievement and might have occurred some years before (Tandon, 2018; 267). Defeat in this battle also explains why after this, Mihirakula was consolidating his power in west Punjāb and why even though he was now the head of the confederation of the Alkhan rulers, he was also a ruler of lesser stature than his father.36

The Effect of the Gupta-s

As previously mentioned, Toramāṇa had given the permission to his subordinate rulers to complete or build their temples – both of the temples were incidentally of Bhagavān Viṣṇu. According to Bakker, this sympathy towards the Vaiṣṇava-s had a deeper meaning and a deeper reasoning, connected with these were his political aims. Bakker in his scholarly work has proposed two interesting claims – one is, as just mentioned that Toramāṇa was somewhat sympathetic to the Vaiṣṇava-s and the other that his aim was not to destroy the Gupta Empire but to take over it and to turn it into his own advantage (Bakker, 2020; 77). Probably by supporting Vaiṣṇava shrines, Toramāṇa was attempting to support the imperial god of the Gupta-s who as we know for most of their history were Vaiṣṇava-s. His attempt to claim the legacy of the Gupta-s is also seen in another evidence, pointed out by Bakker to support his theory, that curiously Toramāṇa no longer uses the clan name Alkhan on his coins (Bakker, 2020; 77) and also is the first one to imitate the Gupta-s in his coinage (Bakker, 2020; 77-78). Toramāṇa was trying to adopt the legacy of the Gupta-s.

“The assimilated Hun not only wished no longer to be reminded of his ethnic background, on his Prakāśāditya dinārs the Garuḍa standard replaced the Alkhan symbol or tamgā.37

The Śaiva Influence

Another equally interesting point that emerges in this period is the influence of Śaivism. Scholars like Hans T. Bakker and Elizabeth A. Cecil are of the opinion that the later Aulikara-s and the family of the Naigama-s provided royal support to the ascending Śaivism which in this period, provided the inspiration to rule out the invaders. Even though, this sect of Hinduism had ancient roots, its increasing popularity, particularly of the Pāśupata sect, at that time is undoubtable. The later Aulikar rulers now seemed to have embraced Śaivism (Bakker, 2020; 87) and they were not alone. The spread of the Pāśupata movement in the western regions of India – the current Rājasthāna and Gujarāt with their network of temples and maṭha-s, according to Bakker (Bakker, 2020; 87) were significant for counteracting the Hūṇa advance further deep in the mainland India. Even though starting as an ascetic movement, its later support by the large section of the population had brought something new to the table. Śaivism says Bakker, had provided the ritual and practical means to attain worldly ends, something that Buddhism seems to have been lacking (Bakker, 87). Probably this is the reason says one scholar that ‘From this period Śaivism is the most dangerous religio-political challenge to Buddhism’.38

Madhyamikā (Nagarī), the ancient city located near Chittorgarh in Rājasthān provided proof of the popular and royal support for Śaivism in this period in the form of a record of a foundation of a temple dedicated to Bhagavān Śiva. Bakker informs that as per the record available, the construction was commissioned by a member of the Naigama family (Bakker, 2020; 87) who might have been related to the viceroy (rājasthānīya) Bhagavaddoṣa under Aulikara ruler Prakāśadharman (Bakker, 2020; 87). There is one other significant indication for the royal support to Śaivism by the later Aulikara-s. Bakker suggests that the colossal stele of Śiva Śūlapāṇi in Daśapura (Bakker, 2020; 90) which also belongs to this very period might have been the main image installed by Bhagavaddoṣa, the viceroy of Prakāśadharman as mentioned above (Bakker, 2020; 90) in Prakāśeśvara Temple, built in honour of Bhagavān Śiva after the battle in which Toramāṇa was defeated.

Another interesting point related to the support for Śaivism also comes from the later Aulikar-s. Bakker suggests that Bhāravi, the composer of the famous epic poem Kirātārjunīyam may also have resided in the court of Yaśodharman (Viṣṇuvardhana), the successor of Prakāśadharman. And Bhāravi was not the only one, Harṣacarita, the famous work of Bāṇa also shows that Pāśupata-s were an important sect of Hinduism at this time.

Along the western trade route or the western regions of India were the main regions where the Pāśupata movement, which originated in south Gujarat in the second century AD, spread to the north.39 Prakāśadharman commemorates his significant military victory over the Hūṇa invaders with a temple to Bhagavān Śiva.40 While worship and reverence for other religious sects within Hinduism and also to other Indo religions was continued by the Gupta-s, it was clear that Vaiṣṇavism had its special place in the empire. After the Gupta-s, the successor states that were emerging in this period were overwhelmingly Śaiva in their religious inclination. For these successor states, which included the future major kingdoms and empires of Indian sub-continent, Bhagavān Śiva signified benevolence, protection and alleviation of pain (Cecil, 2020; 69-70), but he also increasingly at the same time signified unassailable power and dominion.41

Another interesting development we see is that as the Rīsthal Inscription records, spoils of war were taken from Toramāṇa as ritual gifts to be offered to deities (which in this case was Lord Vṛṣabhadhvaja i.e. Śiva) (Cecil, 2020; 64) and offering of some commodities were also made to the ascetics. However, this does not mean that previously such ritual gifts from the spoils of the war were not offered to other gods and deities. It is just interesting to note that religion, in this case Śaivism seems to have been a clear motivator to those fighting the invaders and interestingly to the invaders themselves. The Later Aulikara-s and other successor states found their vigour and strength in Paśupati, the god to whom even the Hūṇa kings bowed down (Cecil, 2020; 67).

“Having seen the success of the rulers of Daśapura against his father, and understanding the spirit of the age, the Alkhan king had embraced Śaivism and its ideology of power (Bakker, 2020; 93).”

We had just noticed how Toramāṇa had been sympathetic to the Vaiṣṇava-s, probably as an attempt to embrace the legacy of the Gupta-s. Similarly, Mihirakula, who we know embraced Śaivism, was probably trying to embrace the changing environment of India at the time in which Śaivism was becoming prominent. Though, in both the cases i.e. of Toramāṇa and Mihirakula, real piety and devotion towards Viṣṇu and Śiva respectively cannot be ruled out but it does seem like political reasons were affecting their religious decisions.

Conclusion

This study shows that many a times, important events in history are much more likely to be part of a larger scheme and there development can be seen happening gradually. Toramāṇa consolidated his power in the Indian north-west and finding his appropriate moment when the Gupta-s were struggling, and probably supported by his allies the Hephthal Huns north of the Hindu Kush, he invaded deep into India and was for a long time undefeated, but he was not unchallenged. His victories, however, were to be short lived when Prakāśadharman the Aulikara rose to the challenge. A terrible battle was fought in which Toramāṇa was defeated and it was now left to his son Mihirakula to consolidate his remaining power. The Gupta-s on their end, weakened by the invaders’ attack and now under the leadership of Narsiṃhagupta Bālāditya were buying time to prepare themselves. They were not to remain under the domination of the Hūṇa-s for long. And fifteen years later, Yaśodharman, another scion of the house of Aulikara-s was to be the last nail in the coffin of the Hūṇa power in India.

References

- 1 Salomon, 1989. p. 7

- 2 Bakker, 2020. p. 26

- 3 ibid.

- 4 Bakker, 2020, Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia, 2020. Chapter X – Indic Sources, p. 280

- 5 Bakker, 2020. p. 27

- 6 ibid. p. 59

- 7 Dezső & Hidas, 2020. Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia. Chapter X.1 , p. 296; also see Majumdar, 1970. p. 35

- 8 Bakker, 2020. p. 62

- 9 ibid. p. 67

- 10 Majumdar, 1970. p. 29

- 11 ibid. p. 31

- 12 Dubey & Acharya, 2014. p. 1

- 13 Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Volume 3 (Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings). 1981. pp. 355-358

- 14 ibid. pp. 358-360

- 15 Bakker, 2020. p. 68

- 16 ibid. p. 28

- 17 ibid. p. 80

- 18 Bakker 2020, Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia. Chapter X. 2, pp. 338-339

- 19 Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Volume 3 (Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings). 1981. p. 352

- 20 ibid. p. 354

- 21 ibid. p. 353

- 22 Tandon, 2015. p. 647

- 23 ibid. p. 649

- 24 ibid. p. 651

- 25 ibid. p. 652

- 26 ibid. p. 653

- 27 ibid.

- 28 ibid. p. 651

- 29 Jayaswal, 1934. p. 64

- 30 Balogh, 2019. pp. 28-29

- 31 Bakker 2020, Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia, Chapter X. 2, p. 333

- 32 ibid. p. 337

- 33 ibid. p. 338

- 34 Bakker, 2014. p. 33

- 35 ibid. pp. 34-35

- 36 Bakker, 2020. p. 92

- 37 ibid. p. 78

- 38 ibid. p. 86

- 39 Bakker, 2014. p. 34

- 40 Cecil, 2020. pp. 69-70

- 41 ibid. p. 67

Bibliography

- Bakker, Hans T. 2014. The World of Skandapurāṇa: North India in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries. Brill Academic Publication. Leiden.

- Bakker, Hans T. 2020. The Alkhan: A Hunnic People in South Asia (A Companion to Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia: Sources for their Origin and History). Barkhuis Publishing. Groningen.

- Balogh, Dániel. 2019. Inscriptions of the Aulikaras and their Associates (Beyond Boundaries: Religion, Region, Language and the State, Vol IV.). Walter de Gruyter Publishing. Berlin; Boston.

- Balogh, Dániel., ed. 2020. Bakker, Dezső & Hidas – Chapter X ‘Indic Sources’. Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia: Sources for their Origin and History. Barkhuis Publishing. Groningen.

- Bhandarkar & Chhabra. 1981. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Volume 3 (Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings). Rev. Ed. Archaeology Survey of India. New Delhi.

- Cecil, Elizabeth A. 2020. At the Crossroads: Śaiva Religious Networks in Uparamāla. In Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape: Narrative, Place, and the Śaiva Imaginary in Early Medieval North India (pp. 48–102). Brill Publications.

- Dubey, D. P. & Acharya, S.K. 2014. Raktamāla Copper-Plate Grant of the Gupta Era 180. Journal of History and Social Sciences (Volume V, Issue-1).

- Furui, Ryosuke. 2016. Ājīvikas, Maṇibhadra and Early History of Eastern Bengal: A New Copperplate Inscription of Vainyagupta and its Implications. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 26(4), 657–681.

- Jayaswal, K. P. 1934. An Imperial History of India, in a Sanskrit Text [c. 700 BC – 770 AD]. Motilal Banarasi Dass. Lahore.

- Majumdar, R. C., ed. 1960. A Comprehensive History of India (Volume 3, Part-1). People’s Publishing House. New Delhi.

- Majumdar, R. C., ed. 1970. The History and Culture of Indian People – The Classical Age. Volume III. Bharatiya Vidya Bhawan, Bombay. (First Edition – 1954).

- Salomon, Richard. 1989. New Inscriptional Evidence for the History of the Aulikaras of Mandasor. Indo-Iranian Journal, 32(1), 1–36.

- Tandon, Pankaj. 2015. The Identity of Prakāśāditya. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 25(4), 647–668.

- Tandon, Pankaj. 2018. Attribution of the Nameless Coins of the Archer Type. The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-), 178, 247–268.

I don’t understand one thing , why do historians beleive bhanugupta lost, his inscription clearly mentions of a great victory (not sure against whom) but the mere fact his inscription is dated in Gupta year would have made it clear that eastern Malwa has came back under guptas. Also I personally don’t think prakasdharman victory was that decisive as attested by bakker. His victory was impressive but not as devastating to hunas , he simply managed to push them back from mandsaur. Bakker has a tendency to dramatize various battles specifically related to shaivism followers.

LikeLiked by 1 person